When I was back in the UK recently my dad asked me when I would stop referring to Hebden Bridge as “home” ?

“It will always be my home”.

“Yes, but when you go back to Australia, you refer to that as home”.

“I have lots of homes” I replied, “I am lucky”.

Home is not a place. Home is a feeling.

And so it was, that I found myself musing about the concept of home. Last year I made the decision to begin an unconventional life of travel and uncertainty. I left my home. I sold or gave away pretty much everything that I own and returned to a life lived out of a suitcase.

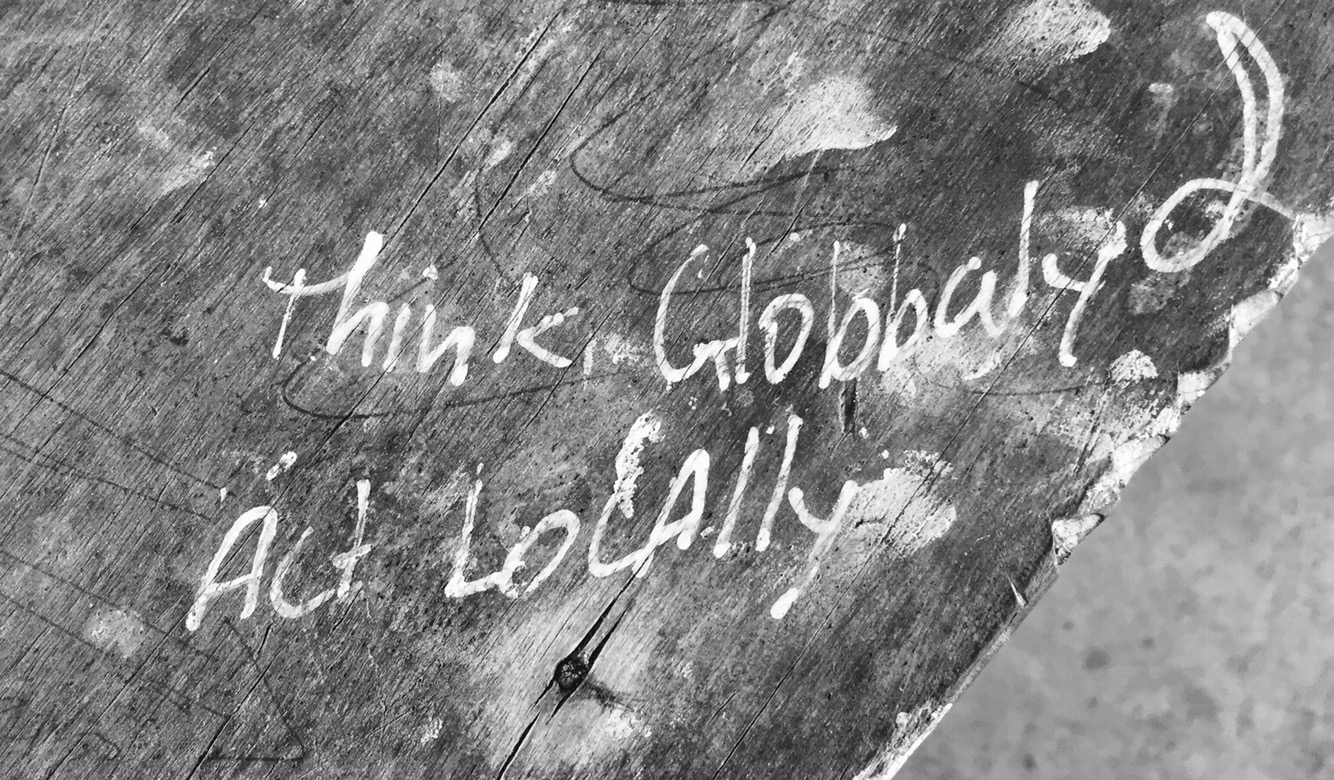

My lifestyle is a choice. It is one that I have been struggling against for years. What is different is that for the here and now, I am OK with who I am, where I am and where I am going. Which seems to be nowhere in particular and yet everywhere all at the same time.

I did not come to this decision lightly. It has taken some years, a few social experiments and many life lessons to dispel my misplaced belief that a) it was time grow up and b) that life decisions were made to last a lifetime.

“We are very good at preparing to live, but not very good at living. We know how to sacrifice ten years for a diploma, and we are willing to work very hard to get a job, a car, a house and so on. But we have difficulty remembering that we are alive in the present moment, the only moment there is for us to be alive”.

Thich Nhat Hanh

I am in my 40’s now.

Middle aged.

Exactly.

I am only middle aged.

I still have half my life to live. That’s another lifetime again. If I can keep my health, my marbles and my drive for life then the possibilities are endless. And that is incredibly exciting.

This life is not new to me. I’ve spent most of my years in Australia living out of a backpack or the boot of my car. The first five or six years were incredibly exciting. Like an addiction, I started searching for a greater, bigger adventure. I had no idea how to stop. I knew that life had to have some meaning, so I thought I had better try to save the world. I went searching for meaning in incredibly remote, under resourced communities with very little support. Those of you who read my blog from the start will have followed as I came to the realisation that the mission I had set myself was a futile one. I had isolated myself from real life and I was frightened that I wouldn’t be able to find my way back. I think, looking back, it was obvious that my mental health was suffering. It was time to make a different decision.

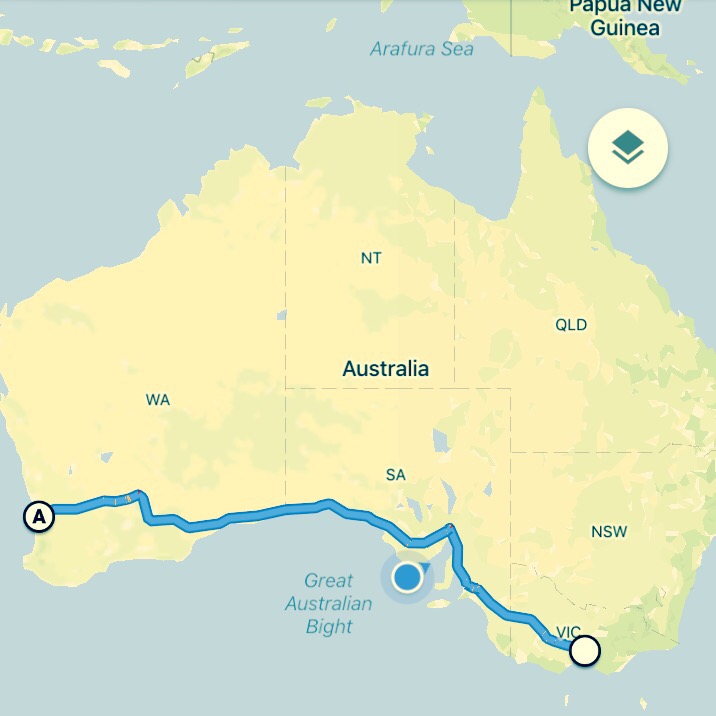

From a remote clinic deep in the heart of Kakadu, I did something I had not done for many years. I made a commitment. I packed myself up and headed off to the sheep farming capital of country Victoria.

I rented a quaint white weather board cottage with wisteria blooming over the gate post and a huge tree in the back yard perfect for whiling away sunny days in the hammock. I worked in a small but busy emergency department, and I went back to university. What I wanted was some nurturing. What I got was a job I didn’t know I needed, seasons, cold weather and sunny days, warm fires, hearty meals with red wine, camping, company, and a good dose of hiking country to sort out the noise in my head.

What I also got, in abundance, was the best, honest, laugh until my sides ache friends that a girl could ask for.

I had lost my confidence somewhere along the line and I couldn’t have chosen a better place, or better people to rebuild it with.

With my newfound confidence came the inevitable drive to explore new horizons. I had stayed for 2 years. It was the longest shot at normality that I’d had so far but somehow, I knew it wasn’t the place for me. I decided that it was time for a new challenge.

I packed what I could in my beloved Bertha and drove north for seven days until I hit the tropics of Far North Queensland. I had decided to step away from nursing and took a job as a Remote Clinical Educator in Cairns. The job involved travelling Australia, teaching emergency and trauma skills to remote area nurses. I had been volunteering for the same organisation for a few years and I loved it. It was the birth of Anna v3.0: Successful Corporate Anna. I cut my hair, changed my wardrobe and rented a stylish beach front apartment.

I spent a fortune creating this new life. I had lived in cheap, brown, broken nursing accommodation and worn a version of pyjamas to work for most of my adult life. This was how I thought it should be, living like a grown-up.

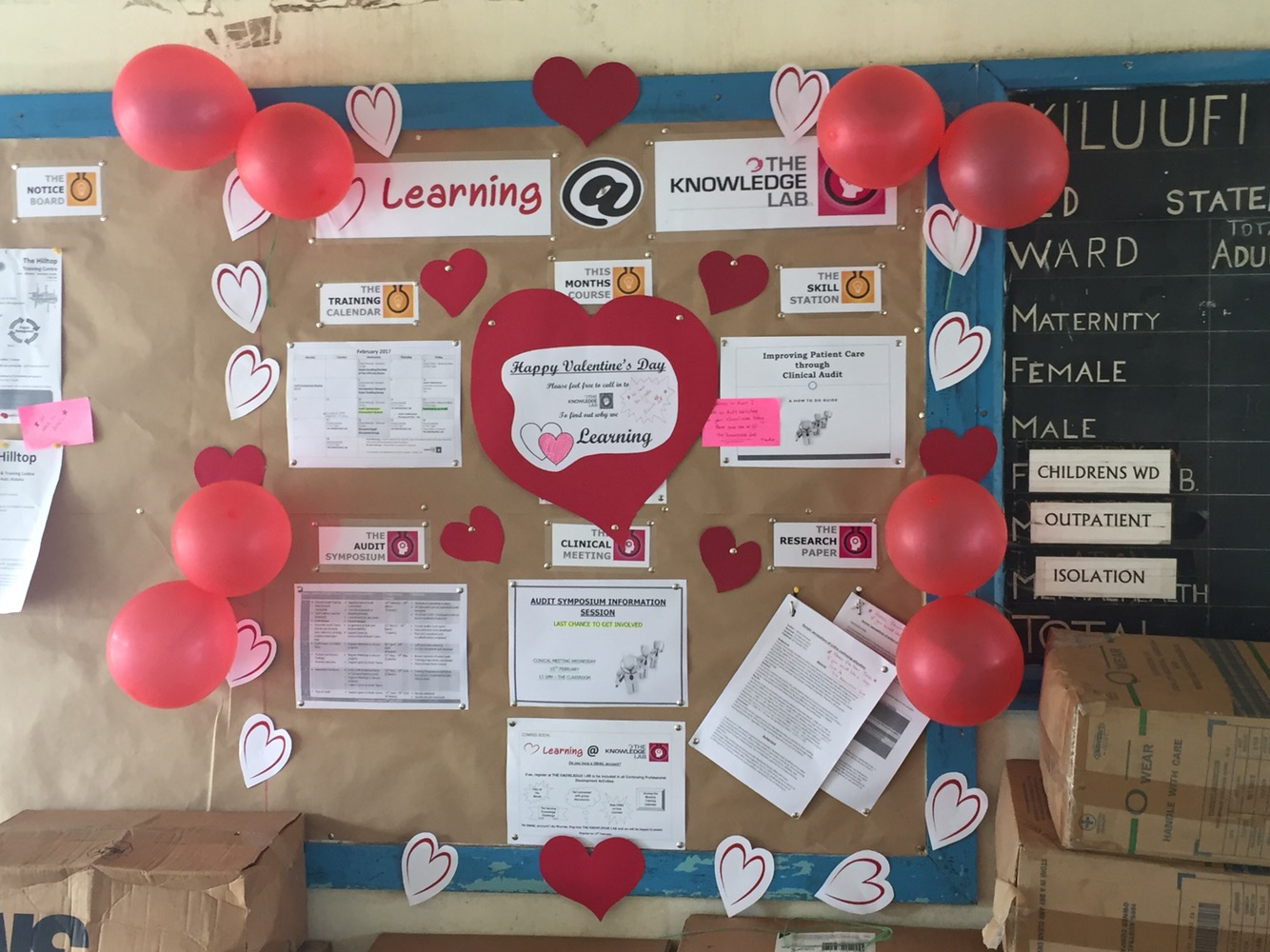

It wasn’t a completely stupid idea. Except that maybe it was. Start with a demanding work schedule, throw in a huge dose of imposter syndrome, add a pinch of failure, hold off on the support and what you’ve got was a recipe for disaster. As with all of life’s little lesson though, what it taught me was, that this version of me, was not me. It was time to look elsewhere.

But where? The answer came unexpectantly. As I fumble my way through this bizarre and unexpected life of mine, I repeatedly keep circling back to the obscure belief that maybe everything does, in fact, happen for a reason. Somewhere, amid this madness, for reasons unbeknown, I had begun studying for a second post graduate qualification in remote health. To achieve this qualification, I was required to complete a clinical placement which was to take me back to the place that I had become most afraid of.

It was a five-hour drive that took me deep into the vast and empty central desert.

A five-hour drive down the endless dusty, rusty, hot and corrugated road with no end. A five-hour drive that ended at a rundown clinic, in a desolate community, in the middle of nothing.

It was a five-hour drive that cemented the belief that this was probably how I would finish my life. Crazy, unsure and alone in the middle of nowhere.

I was a tightly knitted ball of anxiety, the only thing pulling me forward was the knowledge that this was finite. I do my two weeks and I am out. Funny thing was, I loved it. Not only did I love it, but I thrived. I began to see some hope. A tiny spark that maybe I could make a difference and I think, I think for the first time in my life, I felt capable. I knew what I had to do next.

Life’s possessions

I gave my car away and sold the innards of my beautiful beach front apartment. I stripped my life of the bad bits that left me lost and I walked away from Anna v3.0.

I am currently working two jobs. I am without a home and everything I own sits in the corner of somebody else’s bedroom. But right now? I feel like I am in the best place I have ever been. Maybe I will tell you about it sometime?

“Home is not where you were born; home is where all your attempts to escape cease”.

Naguib Mahifouz

When we arrive, it’s like a ghost town. We drive around, beeping the horn to announce our arrival. The one phone box rings out into the silence, searching for a lost soul. In time, you notice the smoke from a smouldering fire as a curious face lifts out of a pile of blankets nearby. A lone figure leans in a doorway. Suddenly, the doors from the shell of a car are thrown open and 5, 6, 7 young children emerge from their makeshift playground. All the dogs come yapping at the wheels of the car as the place starts to come to life.

When we arrive, it’s like a ghost town. We drive around, beeping the horn to announce our arrival. The one phone box rings out into the silence, searching for a lost soul. In time, you notice the smoke from a smouldering fire as a curious face lifts out of a pile of blankets nearby. A lone figure leans in a doorway. Suddenly, the doors from the shell of a car are thrown open and 5, 6, 7 young children emerge from their makeshift playground. All the dogs come yapping at the wheels of the car as the place starts to come to life.

No one puts down any roots. For most people it is a means to an end and they all plan on getting out as fast as they can. Except that they don’t. Because this town can lure you in with a promise of something that we all want: Money.

No one puts down any roots. For most people it is a means to an end and they all plan on getting out as fast as they can. Except that they don’t. Because this town can lure you in with a promise of something that we all want: Money.

Small birds swoop and dive alongside the car. Dragons and lizards of every size and colour warm themselves in the hazy heat on the slate grey road and I marvel at how you can feel so trapped and confined in a town that is surrounded by a landscape that makes my heart sing out with the beauty of what I see and the freedom that I feel.

Small birds swoop and dive alongside the car. Dragons and lizards of every size and colour warm themselves in the hazy heat on the slate grey road and I marvel at how you can feel so trapped and confined in a town that is surrounded by a landscape that makes my heart sing out with the beauty of what I see and the freedom that I feel.  A vast colour palette sweeps throughout this wild and ancient place. It starts with the white and golden sands of the west coast beaches, the turquoise blue of the ocean and the rainbow colours of the reefs that surround the Mackerel Islands and the Dampier Archipelago, providing a spectacular home for sharks, turtles, manta rays, huge whale sharks and shoals of tropical fish.

A vast colour palette sweeps throughout this wild and ancient place. It starts with the white and golden sands of the west coast beaches, the turquoise blue of the ocean and the rainbow colours of the reefs that surround the Mackerel Islands and the Dampier Archipelago, providing a spectacular home for sharks, turtles, manta rays, huge whale sharks and shoals of tropical fish.  It ends with the deep red gorges and the blue/green watering holes of the many national parks.

It ends with the deep red gorges and the blue/green watering holes of the many national parks.

It is summer at the moment and the sun blazes down, most days a hot and humid 40 plus degrees. The red rocks burn my hands as I scramble to the top of mountains or the bottom of gorges, searching for fern lined pools and cascading waterfalls to cool me down.

It is summer at the moment and the sun blazes down, most days a hot and humid 40 plus degrees. The red rocks burn my hands as I scramble to the top of mountains or the bottom of gorges, searching for fern lined pools and cascading waterfalls to cool me down.

Of course, with the hot sun come the desert storms and the torrential rains. Most nights the sky will come alive, like an amphitheatre of lights, the distant thunder rolling on into early hours.

Of course, with the hot sun come the desert storms and the torrential rains. Most nights the sky will come alive, like an amphitheatre of lights, the distant thunder rolling on into early hours. Massive docklands at Dampier and Port Headland house huge cargo ships ready to set sail to the rest of the world. Road trains fill the highways and buses take a steady stream of workers back and forth, 24 hours a day. Everything and everywhere is coated in a fine film of red dust.

Massive docklands at Dampier and Port Headland house huge cargo ships ready to set sail to the rest of the world. Road trains fill the highways and buses take a steady stream of workers back and forth, 24 hours a day. Everything and everywhere is coated in a fine film of red dust.  The deep ugly scars inflicted on this amazing country will be left long after the minerals have gone and the miners have left. Huge holes the size of small cities remain, whole sides of mountains simply cut away, gone forever, and places like Paraburdoo become eerie ghost towns, abandoned as fast as they were built.

The deep ugly scars inflicted on this amazing country will be left long after the minerals have gone and the miners have left. Huge holes the size of small cities remain, whole sides of mountains simply cut away, gone forever, and places like Paraburdoo become eerie ghost towns, abandoned as fast as they were built.