The weekend started abruptly at 3:47am. I woke with a start as my bed rocked, the windows rattled and my shelves shuddered.  The earthquake started with a shaking that varied with an often violent intensity. When the shaking subsided, the rolling waves began, causing the whole house to oscillate back and forth, back and forth. I didn’t move. I just sat there on my bed, riding it out. My thoughts only that this is an inconvenience I could do without. When the eerie silence settled in and all was still, I rolled over and went back to sleep. As the day began to unfold, the only thing that had me worried was my lack of panic. Friends told stories of diving under beds, work colleagues fled from their houses to higher ground, everyone at my guest house was out in the street, the sea had swept far, far out, leaving the ocean floor thirsty and yet I had just sat there. I had done the training, I knew the drill, I had my grab bag packed and still I did nothing.

The earthquake started with a shaking that varied with an often violent intensity. When the shaking subsided, the rolling waves began, causing the whole house to oscillate back and forth, back and forth. I didn’t move. I just sat there on my bed, riding it out. My thoughts only that this is an inconvenience I could do without. When the eerie silence settled in and all was still, I rolled over and went back to sleep. As the day began to unfold, the only thing that had me worried was my lack of panic. Friends told stories of diving under beds, work colleagues fled from their houses to higher ground, everyone at my guest house was out in the street, the sea had swept far, far out, leaving the ocean floor thirsty and yet I had just sat there. I had done the training, I knew the drill, I had my grab bag packed and still I did nothing.

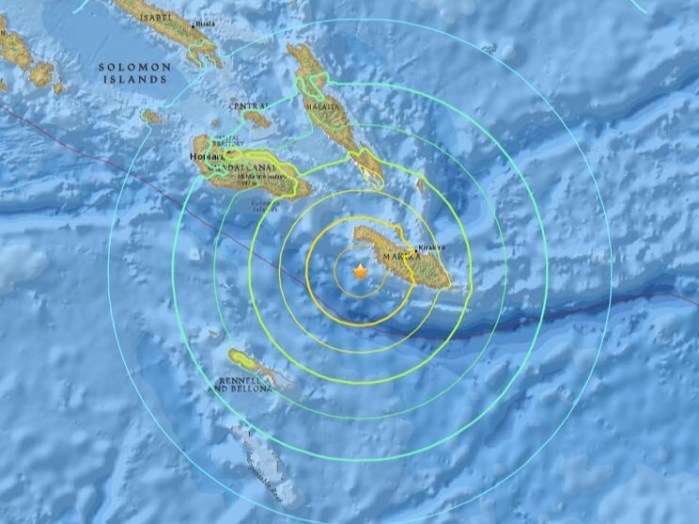

The CNN headline reads:

Massive 7.8 earthquake shakes the Solomon Islands in the south west pacific

The Guadian continues:

The first powerful quake on the early hours of Friday triggered a series of tsunami alerts across the region, sending hundreds of people in the Solomons scrambling to higher ground.

Nope. Not me, no.

My dad sent me a text, and I quote “well, not everyday the earth moves” and the penny drops. My sense of panic? Perhaps it’s genetic.

Thankfully, despite the damage, only one death was recorded. I guess I was lucky. Next time, I will know better.

And that is how my weekend began.

This week, my friends, my best friends in Auki left me to return to Australia for good. Although it has been less than 6 months, they have been my guide, my company and my rock. In a place so far from home, where everything is unfamiliar, strange and scary, the friends you find are family. I am gutted to see them go and the apprehension I feel at continuing this journey without them is huge. But for now, we had one last weekend, and we made it a great one.

I am gutted to see them go and the apprehension I feel at continuing this journey without them is huge. But for now, we had one last weekend, and we made it a great one.

We were headed up to Lau Lagoon in north Malaita. It was one hell of a journey to get there but an amazing ride. We cling to the back of the truck as we bump and bang along an unmade road, puckered by pot holes and broken bridges, splashing through rivers and negotiating roadblocks along the way. It is a magical ride as all along the palm lined road small villages appear through the trees, men, women and children stop and look up, laughing and waving as we pass by. There are constant shouts of “arakwa” (White man), naked babies playing, children running, football games, volley ball, women dancing, men chatting, a market, a school, pigs and chickens, fires burning, a busy river, people washing, a waterfall, a white powder beach, the ocean and a choir of voices singing as we pass an overcrowded truck. For four hours, as the world rushes by, there is not a single moment that doesn’t hold something new and exciting to discover.

We drive till the road runs out and the lagoon begins. It is dark now and we are guided by a bright moon and a thousand stars across the silent calm waters. We pass many tiny islands, each one built up rock by rock, until we arrive at Berlin Island, our home for the next few days.

We drive till the road runs out and the lagoon begins. It is dark now and we are guided by a bright moon and a thousand stars across the silent calm waters. We pass many tiny islands, each one built up rock by rock, until we arrive at Berlin Island, our home for the next few days.

The people of the Lau Lagoon are know as the wane i asi (salt water people) as opposed to wane i tolo (bush people) who live on the main land. History has it that conflict between the bush people and the salt water people forced them off the land and into the lagoon. The salt water people would take their canoes to the outter reef and dive for rocks, bring them to the surface and drop them at a chosen site one at a time. They built islands on the reef in order to survive and as protection against further attack and many still live there today.

The people of the Lau Lagoon are know as the wane i asi (salt water people) as opposed to wane i tolo (bush people) who live on the main land. History has it that conflict between the bush people and the salt water people forced them off the land and into the lagoon. The salt water people would take their canoes to the outter reef and dive for rocks, bring them to the surface and drop them at a chosen site one at a time. They built islands on the reef in order to survive and as protection against further attack and many still live there today.

Despite a slight wink to the modern world: the occasional solar panel, the drone of a passing motor boat amongst a sea of canoes, pre-love clothes and the odd contemporary addition to a leaf hut, life here is very traditional, steeped in culture and played out in almost silence.  The best thing, it is barely touched by tourism, keeping it as true an experience as possible. The worst thing, climate change and rising sea levels means the islands will soon be reclaimed by the salty waters from which they came.

The best thing, it is barely touched by tourism, keeping it as true an experience as possible. The worst thing, climate change and rising sea levels means the islands will soon be reclaimed by the salty waters from which they came.

On arrival we are lead by the light of the moon, across the island, out to the garden where we sit on thrones made from rocks among flowerbeds grown in seashells. It is here that we are introduced to the “pirates”, a group of surly looking boys, brothers, adopted by this family to help build the island, their eyes cast down and thier postures austere. They would like to welcome us with a song. As they serenade us with a lone guitar and a song of love, their vulnerability is laid bare and there is not a heart that can hide from being touched. I can tell from this moment that this is the most amazing, magical place.

The days are simple. We dine on huge fish and seafood cooked on an open fire, tearing it apart with our hands, the vegetables fresh and the fruit so sweet. It is wet season and it rains and it rains. We shelter, drinking hot toddies and putting the world to rights. Or we sit by the light of a kerosine lantern playing board games into the night.

The days are simple. We dine on huge fish and seafood cooked on an open fire, tearing it apart with our hands, the vegetables fresh and the fruit so sweet. It is wet season and it rains and it rains. We shelter, drinking hot toddies and putting the world to rights. Or we sit by the light of a kerosine lantern playing board games into the night.  I am nostalgic for family camping trips in England as a child.

I am nostalgic for family camping trips in England as a child.

In moments of sunshine we head out snorkelling on the surrounding reef or sit on the lawn eating cheese and reading magazines. We visit a market where the only currency is trade and we take boat rides, navigating our way through mangrove lanes to hidden villages.

We visit a market where the only currency is trade and we take boat rides, navigating our way through mangrove lanes to hidden villages.  At night we sleep in leaf huts, lulled to sleep by the gentle lapping of the lagoon waters against the shores of our tiny island.

At night we sleep in leaf huts, lulled to sleep by the gentle lapping of the lagoon waters against the shores of our tiny island.

All too soon I am back on the boat, across the lagoon, bouncing along the unmade road, passed the villages, over the bridges, through the streams and home, back in my room, alone again.

And my friends have gone. Time is an illusion. One day you have a sackful to throw away, the next your hands are empty. You wonder if you used it wisely enough, did you savour every moment? I’m not ready to do this alone, I’m afraid, I’m about to panic. Then I hear the voice of my dad “Well, sounds t’me y’ave no choice. Y’can either worry about it, or Y’can get on wi’it.” Do you know what? he’s bloody right. Harsh, but right. That’s my dad. So, get on wi’it I shall.

And my friends have gone. Time is an illusion. One day you have a sackful to throw away, the next your hands are empty. You wonder if you used it wisely enough, did you savour every moment? I’m not ready to do this alone, I’m afraid, I’m about to panic. Then I hear the voice of my dad “Well, sounds t’me y’ave no choice. Y’can either worry about it, or Y’can get on wi’it.” Do you know what? he’s bloody right. Harsh, but right. That’s my dad. So, get on wi’it I shall.